Most people who are not artists quite reasonably think that artists make things: A painting, a sculpture or some object that is dashed off with brio and creativity, probably pained over, and presented at the end of the process as a finished object or image, a work of art.

What becomes clearer as artists struggle on in the art-making enterprise is that the thing itself, the art object, is not enough. Art is understood, received, rejected or canonized mostly because of something else, which I try to understand as Context. In other words, we appreciate art for a whole cluster of attributes of the art, only some of which have to do with the image or thing itself. This can be a huge challenge for an artist.

Context has many facets: some of the easy ones to understand are, where am I seeing this work of art? Is it in a well-known gallery or museum? Perhaps in a dynamically designed living space or set in the manicured grounds of a famous collector? Is the artist already famous? Or instead, maybe it’s hung in a noisy cafe or sold by the artist on a sidewalk in Midtown. Either way, our feelings about the work can be influenced by the physical setting, and by some implied reputation or selectivity we attribute to the work based on where we find it.

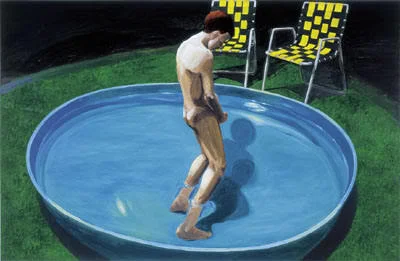

Eric Fischl, Sleepwalker

Context can work inside the work itself, too: my painting of a man with a hat carries different meanings depending on whether the background is some psychedelic orgiastic party or a day out at a Yankees game. Eric Fischl created a huge following for paintings set in disturbing or dysfunctional suburban settings (visual/symbolic context) , that also placed his work in a cultural context that happened to resonate with urban prejudices about tract homes and suburban living. Jeff Koons’ use of mirrored surfaces literally puts the viewers image into the context of, or into his or her experience of the work.

But Context goes deeper. One thing people love to know is something about the artist. Did she hang out with Jean-Michel Basquiat on the Lower East Side in the 80s? Was he connected to Joseph Beuys’ inner circle? Did he drink with Franz Kline and the AbEx giants at the Cedar Tavern, or wander the streets of Montparnasse between the wars? These inform our understanding of the historical and cultural milieu in which the art incubated – maybe we feel a little of the soul of that time and place in the work as a result. But most of this contextual glow is attributed in retrospect: artists hang out in a lot of seedy places that never end up doing their health or their reputations much good.

I think we are all vulnerable to feelings about the art based on things we know about the artist personally. It is not uncommon to see wall text now tipping us off to an artist’s gender, identity, cultural, sexual, political or other markers which presumably are meant to help us gain a deeper experience from the work, maybe even find absolution in it. The art experience can feel like fingers strumming cultural strings, setting off harmonic tones as we observe – “Ah, this is work by a gay Latino incarcerated terrorist – Wow!” (True story, btw).

Jimmie Durham, Arc de Triomphe, 2007

I was marveling over some sculptures and video I saw recently by Jimmie Durham, in Shanghai. I loved the work, but I was not familiar with him. Was he German? English? No it turns out he was American though he had lived outside the U.S. quite a bit. Digging a little deeper… Ah, and he is Native American, Wow! This work now has an almost- shamanic power over me, and I suspect on others who learn this about his ethnicity. Should it? I admit to being vulnerable to this element of Context. These are feelings I bring to the work based on what I’m told about the artist, probably not by anything objectively “in” the work at all.

But there is no formula. Certainly I don’t have these feelings about the work of all Native American artists, for instance. Strong work and having the right socio-political check boxes isn’t enough, either – the work also has to speak in a dialect that is timely, privileged by the curator or other taste-making gatekeepers – the dreaded Fashion dimension of art, where nothing much matters about the work or the artist except that they be in vogue.

Donelle Woolford, Valentin Gallery

I think these issues of context were some of what Whitney Bienniale curator Michelle Grabner was trying to get at by including the works of Donelle Woolford/Joe Scanlan on her floor this year. Scanlan, a white Princeton art professor, hired a succession of African-American actresses to play “the artist Donelle Woolford”, going to openings and press performance events acting as the creator of works produced by Scanlan himself, who was generally in the background as a sort of mentor/associate. Scanlan a notorious trickster, seems to have designed these situations to get the art world to examine this aspect of itself: By appropriating the identity of Donelle Woolford, he appropriated the context which he was pretty sure the art world would accord this work if it were authored by a young African-American woman, but which might not otherwise attach to the work if it were understood to be created by a white middle-aged heterosexual American male.

All this starts to beg the question of how much artists themselves can actually do to make “better” art (or at least better-accepted art) if so much of the eventual impact of their work is determined by contextual forces beyond their ability to manage or change. Still we keep doing the best we can. And maybe I have to spend a little more time trying to find the next Cedar Tavern, and getting a seat at the bar. (It’s probably somewhere in Bushwick?)