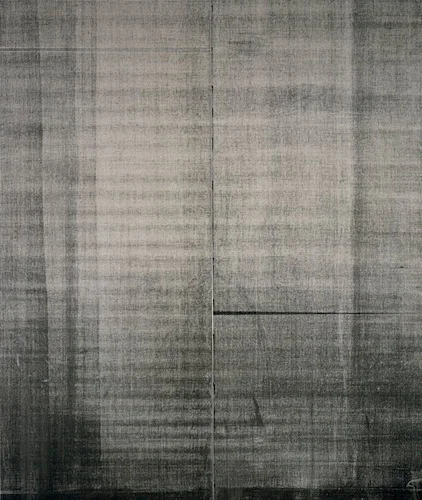

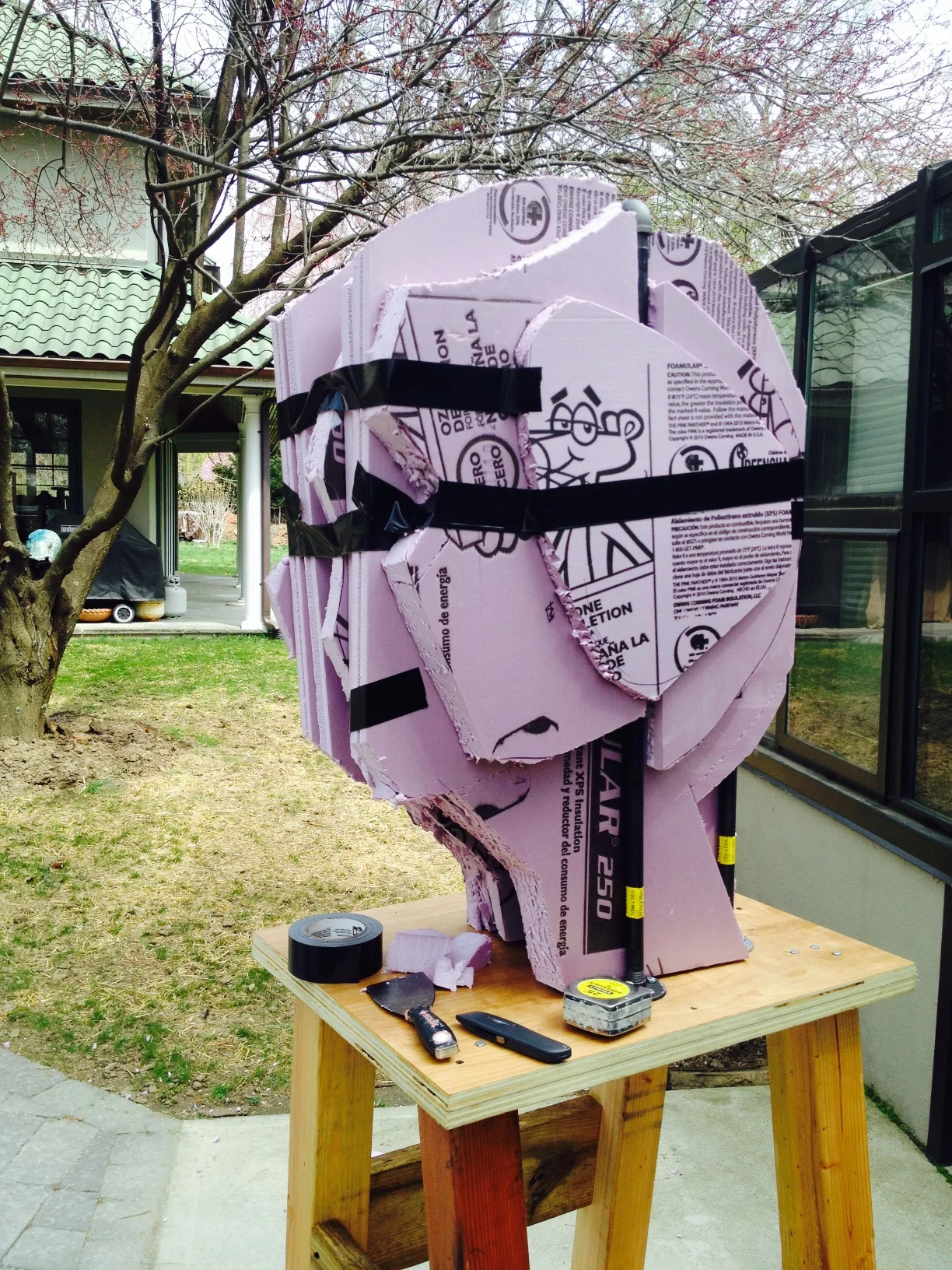

Mel, modeling for a head sculpture, Mel, Side Pony

Much of my work is done with a model, and I realize people may be interested in what that process is like. Most of my models are recruited from our local arts college, SUNY Purchase. Students and recent graduates appreciate the chance to earn a good hourly wage and be part of the art-making process. I learn a lot from them too, as we always seem to have lively wide-ranging conversations during the 3-5 hour modeling sessions.

Mel, Side Pony, (Study) stoneware, 9"H

I like to show the models a range of my work and get to know them because the model-artist relationship is fundamentally a collaboration, or at least has the potential to be. The more they know about my work, my aesthetic, the ideas I am trying to convey with the piece, the better I believe they can contribute to the process.

Emily getting to know my wife at the beginning of her first session

I like to put a model at ease, especially since poses are often done nude. One good way is for people to meet my wife, maybe share a quick lunch and realize that there is nothing sketchy about what we are going to be doing.

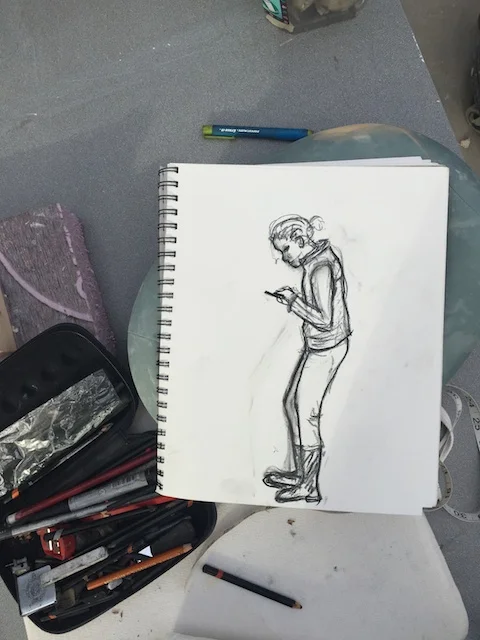

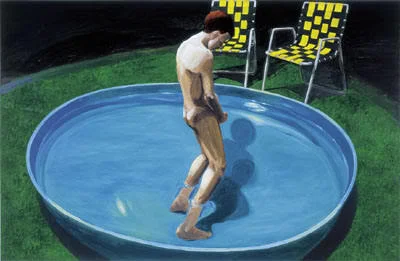

Pose idea -- for a series of clothed figures who will be intently hunched over their smartphones

In the studio we will discuss the piece and pose, and run through a range of options. I may have been imagining a pose but now I am seeing it from all angles and getting the feel for how it will work as a 3-dimensional object in space. Many ideas die here or get radically adapted.

me sketching Emily

rough, fast sketches familiarize me with model and pose

When we are close to something that I think can work I like to draw the pose from a variety of angles. These are quick drawings done to familiarize myself with the model’s body, the angles of limbs and relationships between things which will come up when I make the actual piece. The model also has a chance to feel the physical depth and emotional register of the pose, suggest changes and then commit it to muscle memory.

Most of the sculpting thus far has been done with the various 2x4 and other wood boards in the picture, as opposed to finer modeling tools. The head will get re-sized, surface refined and clothing added in future sessions.

Depending on the piece I will then bend an armature into place and get the clay roughed into form. On a smaller piece that will be fired in a kiln, I will have the clay prepared a day or two in advance for the general size and gesture for the piece so it can be modeled without slumping.

looking at the piece in a mirror helps give fresh perspective.

The process itself takes as long as it takes – I may get all I need from the model in one long session or more typically we will have two or more sessions to get through this stage. Hands, face and feet all come last and I will sometimes do them from memory or from another model or out of my head. All the finish work is done without a model though – I want the piece to function as its own whole, so I am referencing the piece to itself for the final tweaking stages which can take a long time.

A few days later after the surface has started to be refined and a few more details blocked in. Clothes will be added at a later stage, and the head is from a different model.

Several more hours with the model refining gesture and form, then additional days spent refining hands, face, feet and surface.

I get two main things from the model, aside from the inspiration of the interaction with another person during the creative process. First is seeing my initial idea for a piece brought to life with the model’s interpretation of it, and bringing those emotions into a gesture and pose. Secondly, no matter how much anatomy a figurative sculptor knows, seeing the formal inter-relationships between the body parts in an actual body will always be stronger than trying to make up a pose from one’s head. How hips actually move in a twist, how the knee bends and the weight distributes, how the back and shoulders move in relation to the neck and hip, or how an elbow sits alongside the body, the chin aligns over the chest – all these interactions are important to get right, I believe, in order to realize the full power of a piece of figurative art.

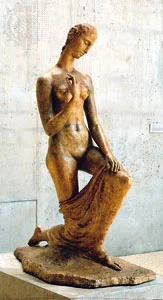

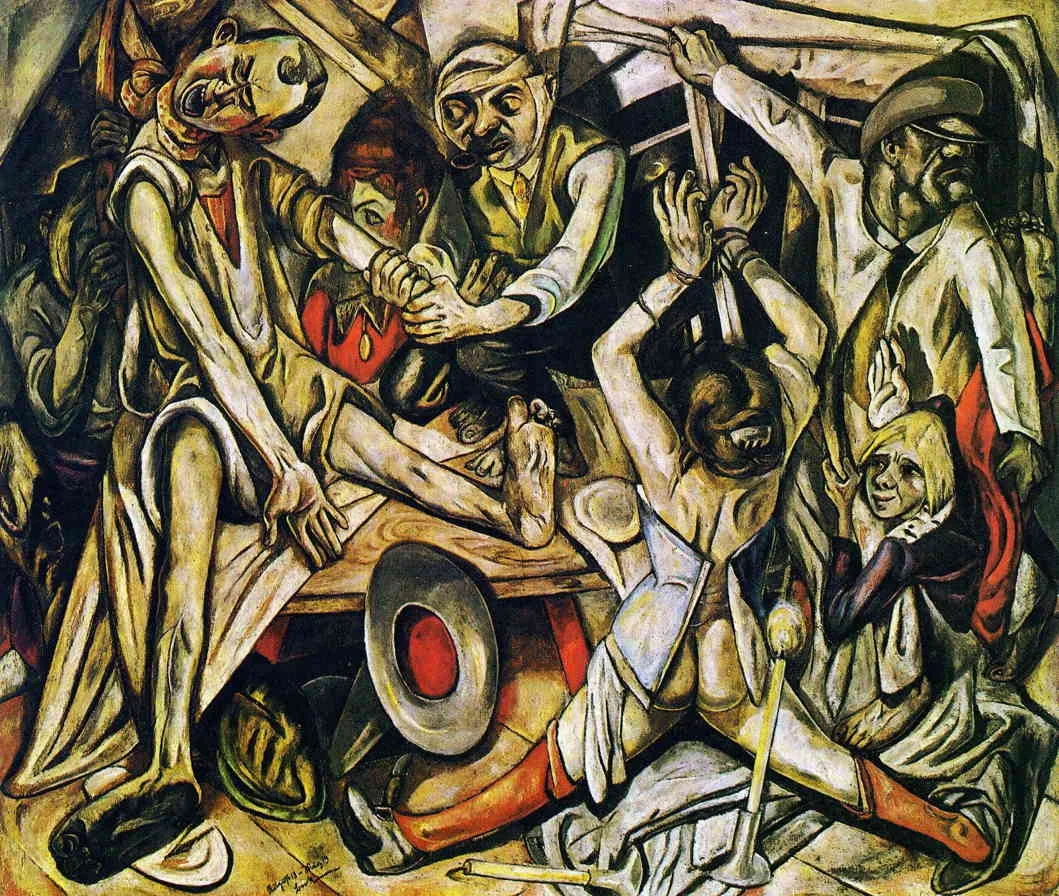

Wilhelm Lehmbruck, Kneeling Woman, 1911

This can put me in a quandary though when it comes to abstracting. If adherence to the actual figure is so important, then it tends to minimize the range for abstraction, and we know abstraction can pack its own power. I have tended to abstract through the use of surface and material rather than the form itself, maybe loosening up detail or bringing surface tooling texture in but only a little. Think my shiny mirror-coated or raku-fired figures instead of emaciated elongated Giacommetti’s. But clearly Giacommetti, Moore, Lehmbruck, Lachaise, Botero, et al abstracted the figure to powerful effect. They also used models (in and out of bed!) so what was it they were seeing that was so different? One factor may be simply that Modernism held sway so various forms of abstraction were de rigeur; the models then were inspiration and point-of-departure. Anyway this is still confusing to me and is an area I need to explore further.